-Professor David Carl, Saint John's College at Santa Fe

War and Agony: The Martial Arts of Hellas from Achilles to Khilon, 1220 to 323 B.C.

For purchase options go here

|

Achilles' call rang out and in answer the fastest drivers surged forward.

|

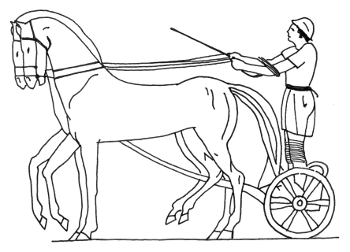

It is possible that chariot-racing was the first Olympic sport*, and it is well-known that chariot-racing was the most popular mass-entertainment in the age of Rome. However, the variety of rigs entered in various Olympics and the heavily-financed super-carts of the Roman circus are not important to this discussion. What is of interest for those of us studying the evolution of prize-fighting arts in ancient Greece, is the nature of the war-cart depicted in Homer's Iliad.

The Homeric chariot seems to have been of the light two-horsed variety used by the Minoans. This buggy was easily transported by sea in small ships as a "kit". It was a light, easily crated vehicle somewhat analogous to the U.S. military's jeep of the World War II and Korean War era. Its Roman counter-part was the biga, a light civilian transport used for municipal transportation in late antiquity. This is not the 4-horse-power race-car of Ben Hur, or the heavy scythed war-cart employed by the Great Kings of Persia. The vehicle in question is a light 2-horse-power rig, piloted by a skilled driver who, if he engaged in combat, only did so as a rescue pilot or as a casualty. What is the significance of such a chariot to the evolution of the combat arts? This apparently trivial question is actually quite important, for boxing only appears in the ancient world after the appearance of the war-chariot, and all-power-fighting evolved [in part]from boxing. To determine if this occurrence is coincidental or causal, one must consider the war-fighting capacity of such a machine. But first let us examine the Homeric military which utilized the war-chariot.

The "armies" of The Iliad are in essence nothing more than bands of pirates and bandits that demonstrate a primitive level of group cohesion more reminiscent of modern street gangs than of modern military units. The armies of The Iliad are feudal conglomerations headed by chieftains who behave more like gangster rappers fighting over "hip-hop honeys" than captains fighting for strategic and tactical objectives. In this context, the importance of this curious personal vehicle becomes clear.

The chariot only thrives as a weapon in an environment where horses are two small to be ridden individually, and began fading from the battlefield just after the composition of The Iliad. A chariot was never an effective shock weapon—and shock** was the element that won ancient battles—because of the poor maneuverability of fixed-axle vehicles, and because the power supply [horses] was entirely vulnerable to enemy weapons due to an exposed position in front of the actual weapons platform. These considerations leave three possible effective uses of the light chariot as an engine of war: as a missile platform, that might be halted a bow-shot from advancing infantry just long enough to loose a volley of arrows before repositioning [the WWII scout jeep with mounted machine gun comes to mind]; as a mobile command post as depicted in the 2004 movie Troy, starring Brad Pitt; or as a means of transporting a heavily armored foot-soldier to and from a battle or duel.

This last seems to have been the Homeric use of the chariot. In a war of personal challenges and muscle-powered combat, the ability to show up fresher with heavier gear than your foot-slogging opponent would constitute a significant advantage for the chariot-borne warrior; effectively putting the wealthiest fighters in a class of their own. In this way, such a device for inserting and extracting highly effective fighters into and out of battle, would encourage dueling on a grand scale. In such a martial atmosphere boxing might well become a pastime second only to chariot-racing, for dueling with ancient hand weapons necessitates the ability to circle your opponent [individual behavior at odds with the mechanics of mass battle.] The shorter one's weapons, the more pressing is the need to circle. Just as modern boxers enjoy advantages over modern fencers when the two meet in bouts with ancient weapon systems, ancient boxers most certainly fared better on the dueling ground than in the push and grind of mass battle—and the chariot was a warrior's ticket away from the press of battle to the coveted dueling ground where risks were more tolerably focused and honor amplified.

Not only is there ample evidence indicating that ancient boxing traditions only developed in Mesopotamia, Asia Minor, Crete, Egypt, Greece, India [and possibly China] after the advent of the chariot, in all of the five Western societies listed above, the rise of boxing is contemporary with, or immediately proceeded by, the ascendancy of a chariot-borne warrior-class. Beyond these circumstances—which could be viewed as evidence of a parallel rather than as a causal relationship between chariot-warfare and ritual fist-fighting—are the numerous cultural and religious threads that bind these apparently unrelated arts together.***

First and foremost is the presence of numerous parallels in the Epic poetry of Greece and India, most notably between The Iliad and the Ramayana. The many cultural affinities shared by the ruling classes of India and the Macedonian and Greek invaders led by Alexander included heroic foundation myths preserved in the forms of these epic poems, which tell the tragic tales of doomed chariot-warriors whom not even the gods can save from their mortal fate; the worship of many shared warlike deities; the institution of prize-fighting with fists; and a strong belief in combined-arms doctrine among military field-commanders, which was counter to the tribal nature of most ancient military doctrine. In fact, the notion of combined-arms tactics seems to have arisen with the chariot, which was a brittle high-performance asset requiring integrated support systems to maintain viability on the battlefield.

The Hittites, who relied heavily on chariots and professional infantry, and appear to have been destroyed by the Sea Peoples, decorated the King's Gate of the royal city of Hattusha with a guardian warrior holding an ax and making a fist. Although chariot warriors of the second millennia B.C. were primarily archers, their secondary armament consisted of maces, axes and swords. The use of such short clubbing, chopping and thrusting weapons is echoed in much of the earliest boxing art, which indicates that the overhand hammer-fist was much more respected by these earliest boxers than by fist-fighters of any subsequent period.

The most direct indication of martial influence [military, athletic and equestrian] from Western Asia or from a common Eurasian Hinterland is the legend of Pelops [Red-face]. Pelops was a legendary warlord from Asia Minor for whom the Peloponnese [Red-face-island], the very cradle of Greek athletics, was named. He is variously credited with having divine connections, being a victorious charioteer, founding the first Olympics, and fathering sons who went on to found the chief military and athletic centers of the Peloponnese.

In a very broad and deep sense the ethics of chariot warfare continued to echo throughout the civic and military affairs of the greatest empires through late antiquity. The Etruscan and Roman practice of riding in a chariot during victory parades, despite the fact that these people did not use the chariot as a war engine, is telling. As is the practice of sacrificing a chariot horse common to both the Roman Emperors of Italy and the Gupta Kings of India. The huge social phenomena of chariot racing in Rome and the later Byzantine Empire, which remained infused with vicious politics and blood-thirsty racing tactics well into the middle-ages, is indicative of the deep-seated nature of man's obsession with his first true war-machine.

And finally, the most convincing and all-encompassing link between the chariot-warriors who laid the foundations for the ancient world and the art of ritual fist-fighting, remains the multifaceted god Apollo. Apollo was the patron of the Asian Trojans in The Iliad, and may correctly be viewed as symbolizing the legacy of West Asian cultural and martial influences in Greece. Apollo drove the chariot of the sun across the sky by day and through the underworld at night. He was the god of Archery, the weapon of the nomadic charioteer; the god of the bull, the very beast sacrificed for an agon, from the hide of which were made the wrappings for the boxer's fist; the god of boxing who boxed a tax-collecting giant rather than pay a toll; the god of prophecy, traditionally the art of the nomad shaman; the god of music, which accompanied the action of the boxer or all-power-fighter during a bout and the telling of his tale afterward; and the god of plagues, which no doubt ravaged the farming societies who were conquered by the cattle-herding horse-breaking chariot warriors who brought his worship to ancient Hellas.****

The eminence of Apollo as the patron of these many intertwined aspects of suffering and triumph endemic to the life-way of the chariot-warrior did not escape the notice of Homer, and it should not escape ours.

|

—still more Paeonian men the runner [Achilles] would have killed if the swirling river had not risen, crying out in fury... ...'I am choked with corpses and still you slaughter more'... ...'captain of armies, I am filled with horror!' And the breakneck runner only paused to answer... ...Down the Trojan front he swept like something superhuman... ...with high hurdling strides, charging against the river... ...they fled as Achilles stormed toward them, shaking his spear...  |

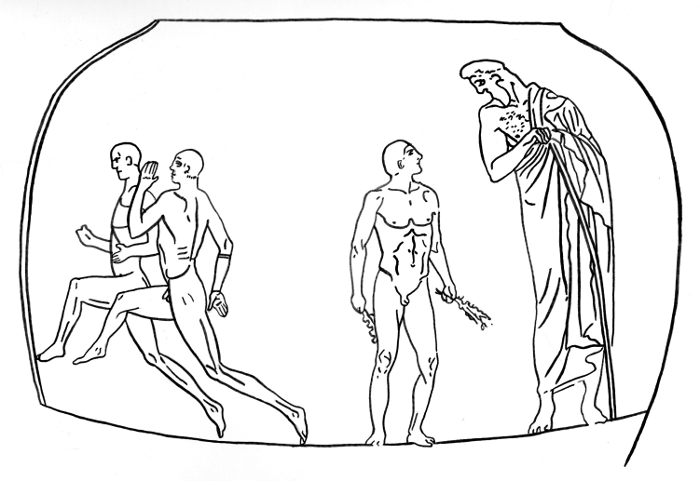

Achilles was the most important Hellenic martial archetype, more important than Herakles or even Zeus, Thunder-Chief of the gods. It was through the example of warriors such as Achilles, able to gain surprise and position due to their foot-speed and then being able to run-down defeated enemies, that the Greeks gained such a high appreciation for the sport of running. Running appears to have been the basic war-art of the Greeks. As strange as this assertion may seem it makes a lot of martial sense.

The first and most obvious link between running and warfare is the preeminence of the spear in Greek warfare from the earliest to latest of times. As any fighting man knows mobility—footwork if you will—is integral to the timing and power of one's strikes, holds and counters. Historically the bow and the slashing sword and the lance have been employed by horse cultures. Cut & thrust swords and shoulder-fired weapons have generally served as the weapon-of-choice for those warriors who marched to battle. However, the javelin [throwing spear] and the thrusting spear was the preferred weapon of the running warrior—typified by the ancient Greeks, the Slavs of the middle-ages, and the modern Zulus. The mechanics of swordsmanship, archery, axe-wielding and flexible weaponry are not compatible with running, as the runner's stride will ruin his stroke or shot. Also, any swings or cuts delivered by a runner will break his stride. The spear, and its cousins the pike and the javelin may be used effectively at a run, individually, and by massed warriors trained to run in step.

The most feared warrior of myth was Achilles—the unmatched runner.

The only spear-wielding warriors to defeat a modern rifle-armed army were the Zulus, who were greatly feared by their Dutch and English enemies because of their extreme running ability.

The most feared military in Classical and Archaic Greece were the Spartans [Rope-Makers] of The Silent Land. But the Spartans most feared by all were the Skiritai, a battalion of 600 scouts, renowned for their running ability, recruited from the mountainous region of Arkadia.

The measure of a spear-man's worth is the shock he can deliver to the enemy at the terminus of his charge and the terror his capacity to pursue will instill in the minds of a shaken or ill-prepared foe. Shock and pursuit are military roles which would be completely usurped by the horse-soldiers of late antiquity and the middle ages. But in a world of mountains, islands and small horses, a foot-soldier's foot-speed was paramount and would form the basic exercise of all combat athletes until the days of the Roman Gladiator.

The stade [root word for stadium or race-course] or sprint prepared one for the charge, the double-sprint for pursuit, and the long-race for scouting and messenger work. The ancient footrace was no more a game to the ancient warrior than the march is to the modern soldier.

|

...Trojan spearmen hurling blows nonstop—a terrible banging about his temples, his [Ajax's] shining helmet clanging under many blows, relentless blows beating his forged cheek irons.  |

Monomakhia [one-to-one-fighting] was possibly the longest continuous dueling tradition in human history. It is a vast subject in its own right which links more meaningfully with gladiatorial combat than with unarmed prize-fighting, although the two are often intertwined. The purpose of this brief piece is to illustrate the causes and effects that the practice of monomakhia had on the art of boxing. All martial cultures possess dueling and wrestling traditions. Boxing is a much rarer phenomena. Generally boxing emerges from dueling or from dueling and wrestling. The first modern boxing champion, James Figg, was a duelist, wrestler and boxer, and was apparently better at dueling than at the unarmed arts. The passage above might give one a sense for the appeal boxing had to the monomakhaist. Boxing as a preparation for helmet contact is an attractive possibility, since its usefulness has been demonstrated to the author on numerous occassions.* Below are some extracts from The Iliad which illustrate uses of the fist in armed combat as well as the oddest boxing match of mythic antiquity. The reader may judge for himself the importance of the fist to the Homeric duelist.

|

...overwhelmed by the crushing power of our [godly] fists!... Achilles had thrust it [his massive shield] forward with his strong fist... ..."But I [Achilles]—whatever fists and feet and strength can do, that I will do, I swear, not hang back, not one bit... ...I'm off to fight the man, though his fists are fire and his fury burnished iron!  |

|

Athena's heart jumped, she charged Aphrodite, overtook her and beat her breasts with clenched fists... ...her [Hera's] left hand seized both wrists of the goddess [Artemis], right hand stripping the bow and quiver off her shoulders— Hera boxed the Huntress' ears with her own weapons.  |

In telling the stories of the boxers, ultimate fighters, pentathletes and wrestlers of antiquity we will occasionally be drawn into the lethal world of the duelist, until, with the tide of Christianity and barbarism that engulfed the pagan world of late antiquity, that dark art that gave birth to the unarmed prize-fighter would ultimately return to reclaim him. By this point in our journey we should already have a clear understanding that the duel is both the beginning and the end of boxing, and that the long-dead subjects of our study understood this intuitively as well as intellectually.

|

But drawing his sharp sword, Achilles charged wildly, hurtling toward him, loosing a savage cry as Aeneas lifted a boulder in his hands, a tremendous feat— no two men could hoist it, weak as men are now, but on his own he raised it high with ease.  |

For the sixth event at the Funeral Games of Patroklus Achilles laid out a single prize, a lump of pig iron. The lump was something of a talisman—a war-prize. It had formerly belonged to Eetion, King of the Kilikians, a famous stone-thrower and father-in-law to Hektor. Eetion was, of course, slain by Achilles, and hence his great iron stone became an Akhaean prize. This iron mass was of great value in the bronze-age, and would also serve as the means—as well as the ends—of contention. The prize was thrown farthest by Polypoetes who surpassed the marks of Epeus, Leonteus and the giant Ajax. Like the other missile weapon arts the diskus throw is treated as a minor event. Battles were won hand-to-hand.

The stone would remain an important weapon in the hands of the slinger and the siege-engineer for many centuries. But the hand-hurled boulder appears to have been a weapon of prehistory that was never important enough to become standard equipment on the bronze-age battlefield. Stone throwing was, however, retained as a martial exercise, with the result that it became a sport, which further resulted in the throwing stone becoming lighter and more aerodynamic. By the 6th Century diskoi were cast of bronze in the characteristic disc shape, measured between six inches and a foot in diameter and weighed from three to fifteen pounds.

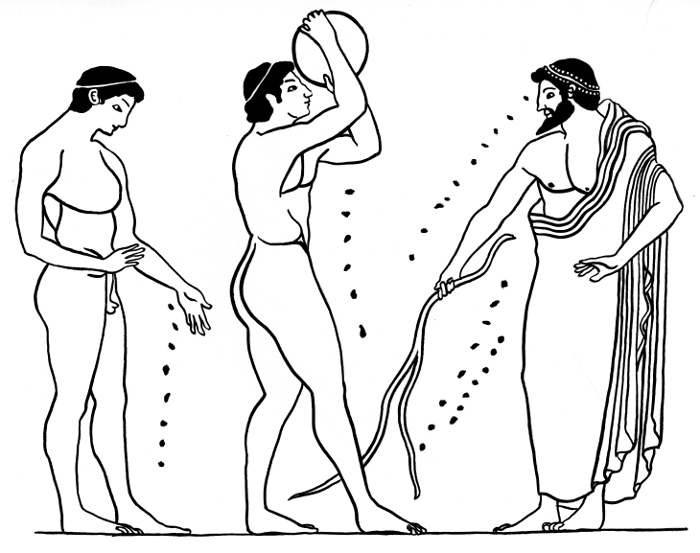

Diskoi of the archaic and classical age were sometimes inscribed and dedicated as votive offerings and not intended for competition at all. They also served a political purpose as the signers of a treaty sometimes immortalized their pact on a sacred diskus. Competition diskoi were revered and dedicated to the god or hero of the game. Although the throwing of these rarified stones was a greatly admired art, the activity seems to have become divorced from any notion of war-preparation and to have become a pure expression of physical culture. However, a good throwing arm is not an altogether negligible asset for a boxer, and the hip torque of the classic discus throw may have been useful in the conditioning of wrestlers.

Although it may be beyond our ability to fully appreciate the art of stylized stone-throwing as a preparation for the martial artist, we should not discount the possibility. Sure, the diskus throw may simply have survived as an eccentric game borne on some stone-age battlefield. But, let us not discount the ancients who—though many centuries dead—are the subject of this investigation. The diskus throw really meant something to the ancient Greek sports enthusiast as demonstrated by the fact that it was depicted in art as often as wrestling, boxing and dueling, and more often than any other martial art of the period.

|

Teuker the master archer took up the challenge, Meriones too... ...They dropped lots in a bronze helmet, and shook hard and the cast lot was Teuker's, he would shoot first...  |

Based on the worth of the prizes [10 double axes to the winner and 10 singles to the loser] archery was still much respected in Homer's time. Archery features more in the exploits of heroes than in athletics [totally abandoned after Homer's day] because it was a lethal killing art, but not an art that won major field battles. Battles were won, and territory taken or protected by breaking the enemy's will and driving him from the field, not by killing. The respect for the individual prowess of the archer and his value as a mercenary soldier on wilderness campaigns [such as the military quests of Alexander] did not translate into archery being accorded athletic status among the Greeks; because the fathers of the Greek city-states wanted their sons to practice arts that would directly enhance their performance as heavy foot-soldiers in the defense or expansion of their homeland. The Hellenic martial artist was groomed to be a protector not a killer.

The bow and javelin were feared weapons, the bow in particular. Apollo, Herakles, Odysseus and Paris of Troy were all feared archers and boxers of myth. The Kretans, renowned as mercenary archers, were also feared boxers. There does not appear to be any functional link between boxing and archery, but rather a metaphorical one. The boxer is likened to the archer who strikes from afar and dodges to avoid harm, just as the wrestler is equated with the heavily armed fighter of the line. There is some evidence that archery—or at least the flexing of the bow—was practiced as a body-building exercise by wrestlers. Flexing a bow would also provide useful exercise for a boxer seeking to balance his shoulder development to avoid chronic rounding of the shoulders, which is a common affliction among modern boxers, though not evident among the ancients depicted in art.

|

Ajax suddenly hurled a glinting spear at Polydamas, fast, but the Trojan dodged dark fate himself with a quick leap to the side—  |

Spear-throwing retained more relevance to the martial culture of Greece because it was combatable with the thrusting spear and the other gear associated with hoplite warfare. Although the Greek citizen himself would fight as a heavy foot soldier who thrust with his spear, his poorer countrymen, as well as soldiers hired from the high border-lands where hunting was still a common way of life, would provide the majority of the fire-power fielded by Greek armies. The wealthiest soldiers of the classical Greek city-states would ride into battle on horseback, often armed with light spears which they hurled from horse-back. Hence the character of military development did not marginalize the throwing spear, and spear-casting remained an admired martial skill for the entire period under discussion.

Functionally, spear hurling might aid in the development of the muscles employed in the art of punching. However, it is just as likely that the javelin was not an art favored by boxers because of the danger of developing a chronic shoulder condition. The particularly demanding shoulder mechanics of the distance throw favored for sport and mass battle would make it an art avidly avoided by professional-level boxers, who, without the benefits of cortisone injections or rotator-cuff surgery enjoyed by modern athletes, would have to look to prevention as their means of defeating that ever-present specter of the athlete—chronic use-induced injury.