For Shoey and Bee

My Friend Shoey

Around 2000 I was just restarting my nonfiction writing career when I was transferred to a City supermarket. A lady named Sharon was filling in for the scumbag manager. She came to me—a simple night clerk who had once been in management—to ask my assistance. There was a new hire who had not been trained. The manager had banked the training hours towards his payroll bonus. She asked me to train the man in a single shift.

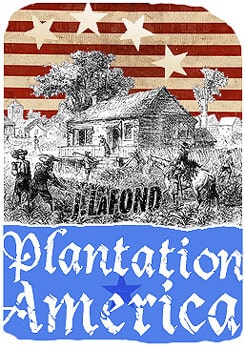

I was soon introduced to Shoey, a jolly overweight fellow who still possessed the spirit of a sprite-like teenager, and still wore the shorts and old style tennis shoes that he had once worn as a street kid in this oldest of City neighborhoods. He was an apt pupil, an intelligent man who wanted to learn a trade. He had spent the last few years caring for his dying mother and ailing brother. He had never had a job. There would be no social security. He had worked all his life, but never ‘above boards’.

Shoey was awed by my ability to track the inventory, move it quickly and precisely, and predict every question that was about to emerge from his mouth as to the most efficient method of doing this or that with that inventory. He then finally stood with hands on hips and extended his hand at the end of the shift. We shook hands and he said, “Thank you Jimmy. This is just a shit job. But it is all I have to keep Mom’s house. I need to be good at it. I know from experience that when you suck at whatever you are doing, that you disappear and no one cares. I really appreciate this brother. How did a long-haired street-thug like you learn all of this shit? Why aren’t you a manager?”

I responded as we held hands between us, not wanting to pull away until I told him the truth, “I was a manager man. I got out of that. Firing a hundred-and-fifty-two guys just ripped a hole in my soul.”

Shoey’s hand went cold and he pulled it away like Little Red Riding Hood retrieving her dainty hand from the wolf’s paw. He winced as I grinned and said with scrunched eyebrows, “Fuck me running! You’re the enemy—employer cop—a supermarket Nazi!”

I grinned and asked, “So how do you feel now?”

He wiped off the hand I had shook like it had zombie juice on it, smiled, looked down at his feet and fingered his chin, shook his head, looked back up at me and grinned. “Shit, it feels like the first time I sold dope to a narc!”

We both laughed and patted each other on the back. He then hugged me and exclaimed, “I guess if I can change my ways you can change your ways. Let me ask you though, would you have fired me, or had me retrained like Miss Sharon?”

I looked him dead in the eye, “I would have fired your fat ass as soon as I saw you lay down to work the bottom shelf.”

He gave the look right back and whispered “You skinny motherfucker! I ought to kick your ass.”

“You ought to man.”

“In the engine room?”

“Yeah man—let’s go.”

He laughed with his arm around me all the way to the engine room. When we stepped in and closed the door and started throwing hands he was in state of ecstasy, an old time karate guy who had never had an honest job in his life, until now, against some straight-edge twerp boxer who had fired over a hundred of his slacker brothers.

Shoey and I walked out of that engine room—having been paid by the scumbag company we worked for at the expense of our scumbag boss’s payroll—the best of friends, as if we had grown up together. Over the next five years Shoey would tell me his life story, over and over again, in the aisle while we worked, with no way to take notes.

I am writing Shoebox as a novelette, with the premise that I actually sat, notepad and pen in hand, at his kitchen table with him, the kitchen table over which the ghosts of his entire family still haunted him, conducting the interview we had always talked about doing but never got around to. Shoey had become a good employee; supporting his new girl, who was also ‘retired’, a former hooker. When I took a management job I hired him so he could make some extra change. He was attacked on the way to work one day and his girl, Bee, called me and said she would not let him come back into the bad neighborhood that I did business in. He was too ashamed to speak with me, having fallen far in his own estimation from the day he and I had rumbled to a draw in the engine room.

After Shoey got word that I had retired to write fulltime he called me to schedule an interview. It was a Friday afternoon at about five. We spoke until six. He was tired, just come home from the hospital after being treated for pneumonia. He wanted to talk longer, wanted me to ‘hop the bus’ to his place and sit at the kitchen table as he repeated his story so I could ‘get it right’. There were things he had ‘left out’. He offered me a place to stay, in his brother’s old room. He didn’t want any rent, just wanted me to protect his ‘Old Lady’ when she went out to the store. He was ‘feeling old, cold, worn out’.

I told him that I had to go—was booked for the weekend and had to get to work in a few hours and needed a nap. Shoey said, “Okay Brother, talk to you soon.”

On Monday morning I was headed home, planning on calling Shoey and scheduling an interview as soon as I got to my desk. My cell rang. It was Steve, a mutual friend. Steve said, “Hey brother, did you hear about Shoey, he died?”

“When did he die?”

“He died in his sleep, Friday evening.”

I felt like an animated corpse walking home, for not hopping that bus and shaking his hand again. It has been over three years now, about time I tell what I can of his story.

I never had that sit down at the kitchen table, never took any notes when he told me his tales in the aisle, or when we sparred in the stockroom, or when we walked through the park after work. So, although I am recollecting his words as best I can, it is mostly ten years on now, and can’t be entirely accurate. I could not sell this as biography as I lack checkable facts, have forgotten names, and most likely have misremembered or transposed some addresses and street corners in my mind. Also, Shoey never did tell me how he ‘got out’ of the drug business. I know why he got out, and where he went, but not how. As biography the story of Shoey has a yawning pit where the apex should be. I will fill that pit in, making this a work of fiction. I will also fill in a few gaps in Shoey’s tale with recollections of other men his age who grew up in that same neighborhood.

That said, Shoebox is the true story of a man who was my friend, with the last chapter being fiction, my imagined version of how Shoey escaped the criminal life to live a good decade with a good woman, like his mother had always hoped.

Book Marks

Dad

Uncle Gus

Danny and Tom

Mister Epstine

The Shoebox

Shirley

The Phone Call

Jake Rudd

Church

Officer Lee

Black October

Rummage

The Katana

Darlene

The Pagans

Brick Wilson

The Recliner

Three Lines

Lou Helms

Charlotte’s Web

Aussie

Mom

Bee

The Way Out