“Cowards die many times before their deaths,

The valiant never taste of death but once!”

-Pierce Egan, on Henry Pearce

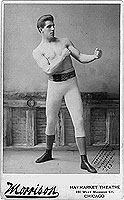

Pearce was a gifted natural athlete, who, like most of his fellow boxers, died of “consumption” before their 35th year. His fights were brutally epic and numerous. He retired undefeated by “death” “that Conqueror of Conquerors,” and was known for heroic exploits outside of the ring.

Although, in the brutally materialistic seat of World Empire, from where a callous hand raped the world, people were not inclined to offer aid to those destitute, dying, sick, or in the process of being beaten and raped or burned to death, the moral squalor of English society, from high to low, did not affect the Fancy so much. While the rich and poor alike scrounged around in the hell of mercantilism, trying to adopt ancient ways to the rising lifestyle of the merchant class, in which things and possessions matters more than anything, the Fancy were sporting men of high and low birth that rejected this material ethic. Prize-fighting was against the law for various reasons, primarily that the bodies of athletes should rightly belong to the army and navy of the king, and that the old values of combat that bound rich and poor together in a common masculine tradition, were a wasteful affront to the security-first sensibilities of the rising merchant and banking classes that actually ruled the kings from behind the scenes. Keep in mind that urban England 200 years ago was the prototype for our more evolved greed-based society, which has gone beyond valuing material beyond all, to actually worshipping it.

Although, in this Proto-Dickensian world the saving of one life was not worth the risking of another, any more than the risking of two lives in pointless competition reflected a desirable pursuit, people were still people underneath their brutalized façade, and thrilled to the heroic act.

Below are two examples of Henry Pearce in action as a lone, poor, white man, adrift in a world that hated him for being poor, despised him for not being in uniform, but none-the-less loved him for being something unthinkably obsolete.

Note that athlete’s in Pearce’s day did not get rich, but simply hoped they would win enough renown and money to be able to run a small tavern in their diminishing years.

November, 1807

On Thomas Street in Bristol, a fire broke out at Mrs. Denzill’s silk mercer. The crowd gathered on the street to watch as the house went up in flames. The fire climbed so quickly that “the servant of the house, a poor girl,” who had gone to the attic to rest, did not wake soon enough to get out. The crowd stood, riveted in horror, about to watch the girl’s immolation as she screamed for help.

She was just a servant, and poor.

Henry Pearce came into the crowd and immediately decided to act. He climbed the adjoining house, got up on the parapet [the low wall on the roof] and hung over, telling the girl to reach out. She did so, and he grabbed her wrists and swung her out of the window and up to the roof to safety.

She clung to him and blessed him.

According to friends this “was the happiest moment of Pearce’s life.”

Fighters and fight fans pooled money to pay for a poem to be published in a magazine, dedicated to this act of bravery. The poem consisted of three verses of six lines each.

December, 1807

Henry was walking over Clifton Downs [near where cattle were grazed at this time, which had formerly been the site of lead mining, and would eventually become a park and residential area] near Bristol. Three “athletic men” described as “game keepers” [professional hunters and anti-poaching police] were in the process of beating and raping a young woman. Pearce was walking, apparently with company, with a dude who had a watch. He was most likely engaged in his conditioning routine, which, for bare-knuckle fighters, was taking long brisk walks, preferably in hilly country outside of town.

Pearce demanded that these men leave the girl alone, and they obliged, by immediately attacking him with “the utmost fury.” Their names were Hood, Francis and Morris.

Three known government lackeys doing this in what amounted to a park, without shame. That should set a certain tone when considering this era.

While Francis and Hood confronted Pearce and traded blows, getting the worst of it, Morris snuck around from behind and smashed Pearce on the head with enough force to “produce a severe contusion.”

Pearce engaged these three men in a 3-to-1 standup fight for seven minutes. That’s right, some busybody with a watch set himself up as fight correspondent on the spot, which brings one to wonder how many folks had been content to watch the beating and rape of the girl.

After seven minutes, Hood ran away, to his everlasting shame. Pearce’s punches were delivered coolly, with precision and were so hard that his opponents suffered sickening impacts. Pearce was the current heavyweight champion, so one might imagine this being an entertaining spectacle for the onlookers, who were very likely guys just following Pearce around wondering what kind of fun could be had. Pearce was even known for accepting fight challenges while he was in bed, and only asking long enough to get dressed before toeing the scratch. [Stepping up to the centerline of a boxing ring.]

For the next eight minutes, Pearce beat Morris and Francis so severely that they were unable to continue. He had knocked them both down repeatedly, but finally, 15-minutes into the brawl, they lay on the ground and begged for mercy.

That’s a man.

Where might I read more information about this interesting character?

Right here, next week, I will cover two of his fights.

His career is covered in Pierce Egan's Boxiana, Volume I.