The story of the rise of civilization—which is mass aggression socially defined—is told within the Epic of Gilgamesh:

Book 1: Focuses on the downward aggression of Gilgamesh against his subjects.

Hierarchal aggression defines civilization.

Book 2: The focus is on mankind’s search for an antidote to the oppressive Gilgamesh—Enkidu, the wild free spirit—the tyrant’s peer in aggression, who becomes the king’s accomplice after they discover they have so much in common.

Horizontal aggression between the ruling class binds the population into factions.

Book 3-5: Focus on man as the predator that challenges his own environment, essentially detailing the notion that civilization itself is a form of aggression against the natural order.

Heretical aggression against the natural order enables man.

Books 6-8: The focus is on the price paid for defying and overturning the natural order.

Hierarchal aggression by the gods is man’s punishment for overturning the old order

Books 9-1: The lesson of the lone vision quest of Gilgamesh is that man will never achieve balance with the natural order in the wake of his disturbing it, unless those who ascend to the highest human positions look upward for counsel and outward for challenges, away from and beyond the world of men, and that only the ruler [top aggressor] of a civilization who does so can alleviate the suffering of his people, to become a deliverer rather than an oppressor.

Aggression should be channeled constructively outward, not destructively inward, in other words, declaring that the apex aggressor in a civilized society will act destructively upon that society unless he is able to find traditional masculine engagement with the higher order beyond the domesticated world of civilized man.

The entire epic is a tale of domesticated mankind as a failed state, without engagement with a higher or outer totality, indicating that hierarchal and horizontal violence are abominations caused by man’s domestication. This fits well with the idea that the first settled people would have folk memories of a time –reflected in the person of Enkidu—when all aggression was outward as the hunting people explored and exploited a wider, wild reality, rather than exploiting each other in a circumscribed, domesticated field of experience. Thus far there is very little evidence to support the notion of primitive peoples employing aggression within their familial group, where it is a gross and ever present aspect of civilized life, with the people of Uruk in the epic shouting so painfully to heaven of their unjust suffering as to stir the gods to action.

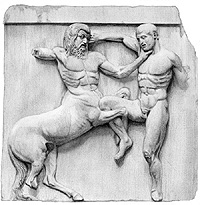

The Iliad

This much-examined epic tragedy seems to confirm the warnings of heedless tyranny among domesticated man as Agamemnon fills the role of Gilgamesh turned distant, materialistic monster—not even much of a man any longer. The corrupting effects of power have diminished this king beyond heroic redemption, so the story focuses on a murderous litany of horizontal aggression between heroes, with the greatest of heroes—the doomed Enkidu as Achilles—sitting out much of the action, as his natural strength is now so far removed from the remote hierarchal structure of the evolved State that he cannot relate to it in terms that are not either monstrous or sacrificial.

Power in the Iliad no longer has a heretical expression, but is exemplified by a manic state of horizontal aggression put into play and managed by a more manipulative hierarchal structure, which relates more to the gods of Gilgamesh than to that proto-king, with the gods of the Iliad reduced to meddlesome caricatures. The entire circumscribed world of man has become merely a matrix for suffering, with mankind cutoff, from or castoff by a greater order, which itself seems to be a gigantic mimicry of the life of humanity.

So, where the violence tree in the epic of Gilgamesh takes the pyramidal form of the pine, with, at its nadir, a downward focus, and its apogee, an upward focus, the violence tree in The Iliad is more of a weeping willow, its spreading branches of horizontal strife eventually sweeping the ground of their own melancholy weight, with no ascendant prospect.

This is Harvard level thesis stuff..you should at least have a six figure gig with some think tank or something..bitches and booze poolside..

Just the semi-emasculated materialist view on it.