Gilgamesh said to Ishtar at the stairs of her temple, “Your price is too high, far beyond my ability to repay. How could I repay you with jеwels, perfumes, robes? And what of me, when your heart turns and your lust burns cold?

“Why should I love a cracked oven that fails to keep the cold at bay, a flimsy door that fails in the wind, a palace that falls in on its occupants, a mouse that chews a hole in its own shelter, the tar that darkens a laborer’s hands, a leaky water skin full of holes, a block of limestone that weakens and undermines the better stone of the wall, a ram that batters down the wall of a friendly city or a shoe that injures the wearer’s foot?

“Of your many husbands, which did you love forever? Could any satisfy your many desires? Shall I remind you of how they suffered? How each came to a bitter end? The beautiful boy, Tammuz, whom you loved when you were young—you sent him to the underworld, his doom to be wailed for forever. Thus your love turned. You loved the bright, spotted bird. Then your heart changed, and you broke his wings. Now he sits in the forest, crying. You loved the lion for his strength. Then your heart turned, and you dug seven pits for him. When he fell into one of these, you left him to die. You loved the furious stallion. When your heart turned, you cursed him to slave under whip and spur, to gallop far with a bit in his mouth, to dirty his own water when he drinks from a pool. The stallion’s mother, mare of heaven, was left to weep without end. Your lover the shepherd, master of flocks, who baked your daily bread and brought you fresh slaughtered, roast lamb—when your heart turned, your touch turned him to a wolf, so that now, his own sons drive him off, and his own dogs nip at his hairy heels. You seduced the gardener, Ishullanu, who tended the groves under the sky, who brought you baskets of fresh dates daily to liven your table—you lusted for him, gathered him close and whispered, ‘Sweet Ishullanu, your rod I shall suck. My vagina you shall stroke, my jеwel you shall caress.’ He knew and answered, ‘Why should I taste of your rotten meal? Your vagina is the repast of dishonor, your wetness—the beer of shame. The blankets of your bed will be as thin reeds against the cold, blowing wind.’”

Gilgamesh continued, “But you kept up your seductive song until he gave in. Then your heart changed, and you turned him into a toad, doomed to live in his own devastated garden. And why should Fate be any better to Me than to them? If I also became your lover, you would treat me with the same cruelty that you heaped upon them.”

Notes

Gilgamesh’s indictment of Ishtar can be taken as a representation of the price of intensive agriculture and of animal domestication—the resulting imbalances that early civilized people encountered. Men of this period had much experience with animal domestication, particularly the horse. Even lions were captured and used to guard city gates. Particular breeds of dogs were bred to counter wolf packs. The submission to the greater good of the city would, to an astute observer, appear to be a similar fate for man as what man had worked on the beasts he had domesticated. Particularly in a walled city, it has been postulated that men initiated marriage customs as a result of their work in animal domestication and their recognition of paternal lineage in their flocks. In this light, Ishtar’s use of marriage might be an ironic reflection on how social controls devised by men to enslave women might have a corrosive effect on their own masculinity.

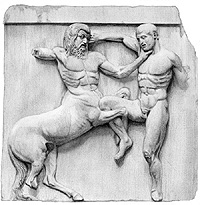

Gilgamesh named six beings against which Ishtar turned her wrath after a declaration of love. Gilgamesh would be the seventh, him stepping into the seventh place, the mythic number of the hero. From the Hellenic tragedy Seven against Thebes, the seven layers of the Homeric shield, the seven-layered hand-strap of the ancient boxer, to the Seven Hills of Rome [no way were they stopping at six], down to such modern cinema as Seven Samurai, The Magnificent Seven and Tears of the Sun, the number of the hero has been the same as the days of the week since Sumerian times.