Who were the opponents and the trial horses of yesterday; of the golden age of boxing? Most would answer, ‘who cares?’

I would disagree. Today an opponent is a boxer with a handful of fights. If you are a champion your opponent has 15 to 25 fights. Before pay-per-view TV fighters fought twice as often as they do now. Before TV they fought every week! This pace got a lot of men killed, and disabled others with boxing dementia. But what it produced was the best boxers that have ever stepped between the ropes. What elevated these superior fighters over our current champions was the quality and variety of their opponents. The Images of Sports series of local boxing books makes these fighters known to us.

Baltimore’s Boxing Legacy: 1893-2003

Thomas Scharf

2003, Arcadia Publishing, Charleston SC, 128 pages

Mister Scharf has assembled well over 200 photos of old-time fighters, fight venues, gyms, tickets, contract signings, etc. This is an actual photo album of over 100 years of Baltimore boxing. Baltimore’s six world champions are covered no more extensively than many of the men they sharpened their skills on. Managers and trainers are also presented in their capacity, which helps trace the history of Baltimore’s East Side boxing tradition.

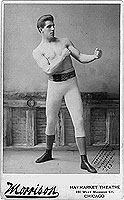

There are a couple of small errors, mostly to do with a fighter’s hometown being confused with the town he fought out of. Overall the research is impressive. Early on you will see many photos of boxers who appeared not to protect their head. These men wore light gloves and used head movement to protect their head while their arms covered their ribs. Just thumbing through the book from front to back will give a nice picture of how boxers evolved their art to keep up with the changing hand gear.

The most notable fighters in this volume are Joe Gans, perhaps the best lightweight ever, George “KO” Chaney, onetime KO king, and World Bantam Weight Champion Johnny Kid Williams. Williams is pictured shaking hands with giant heavyweight Jess Willard. Although the Kid is giving away a foot and a half in height, his hands are just as large as those of the giant. This is the type of thing that you look for when fighters have promotional photos taken, the kind of thing your coach looks for when he is evaluating your possible opponents.

One thing I would like to note, that although Baltimore is now a hotbed of racist tension, and has been for decades, in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries it was the place to be if you were a black boxer, a place where you could get a fare shake. Baltimore boxing fans also benefited from this. Another interesting social note that you always want to look at with boxing is what ethnic groups are dominating at what periods. In the U.S. it basically went Irish, Jеwish, Italian, Black, and then Hispanic over a 150 year period. The interesting thing illuminated by the early portion of this book is how many Italian fighters changed their name to sound Irish.

There is no way you can read a book like this and not appreciate boxing as a social ladder for urban athletes; a small roped off square of the world where men have always been able to find equality, even in the most unequal society. In Thomas Scharf’s book you will find men that are barely a footnote in boxing history with over 100 pro wins to their credit. He has done us a favor by reminding us how hard they worked to build our sport. They didn’t all get to buy that bar they dreamed of, and some died forgotten, in poverty. But every man that made it into this book fought for a slice of immortality that still stands.

Thanks Mister Scharf.